STUDENT SPOTLIGHT: “The God Of Longevity”

“The God Of Longevity: A Study on F.S. Louie Restaurant Longevity” Ashley Killian, Natalie Bravo, Nina Wilson, and Annie Harlan

A History of Chinese Immigration in the U.S.

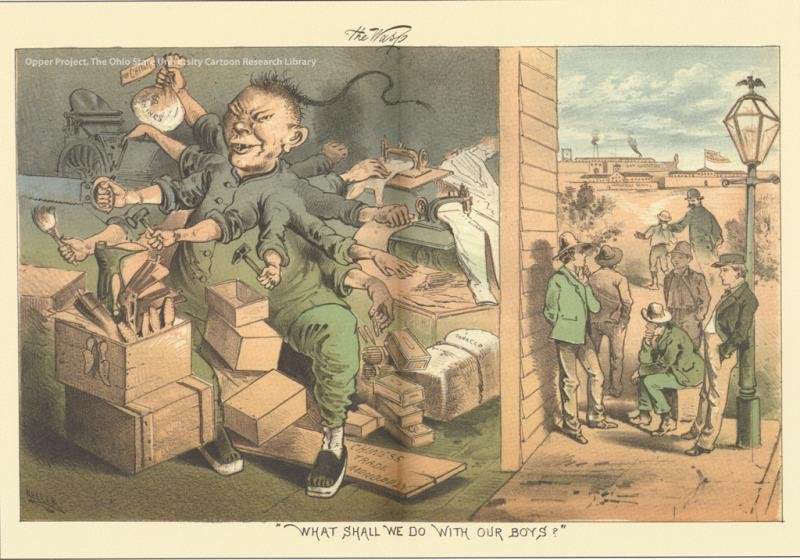

Chinese immigration into the United States began most prominently with the Gold Rush (Frenzeny, 1877). With migrants traveling to the U.S. in search of overnight economic success, many stayed in hopes of making a better life for themselves here (KCC Alterna-TV News). These immigrants often found work in more “undesirable” labor markets, the most prominent being as railroad workers (Chinese Immigration PBS). Despite immigrants working jobs that Americans often did not want, the economic downturn of the 1870s made jobs scarce and led to a rise in anti-Chinese sentiment. Americans spread racist propaganda that claimed Chinese immigrants were stealing American jobs (Keller, 1882). This culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 that barred Chinese immigration into the U.S. (Arthur, 1882).

Although this act halted the number of immigrants coming into America, the immigrants who were already established in America began to come together and form “Chinatowns.” These Chinatowns were typically located in large, metropolitan cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington D.C., Boston, San Jose, and Seattle, (How American Chinatowns Emerged Amid 19th-Century Racism). Chinatowns became homes to a growing number of Chinese immigrant owned businesses. One type of business that became particularly popular was restaurants due to the relatively small amount of capital necessary to open them (Olympia’s Historic Chinese Community – Restaurants). These Chinatowns became spaces where Chinese immigrants could come together and find success and prosperity despite racist ideologies and policies in America and have persisted as cultural and historical hubs across America ever since.

The Rejection of Traditional Chinese Cuisine

At first, early Chinese restaurants solely catered towards traditional Chinese cuisine, which included dishes such as “duck feet, pig stomach, intestines, and fish heads” which only marketed towards other Chinese immigrants (http://conniewenchang.bol.ucla.edu/menus/index.html , December 8, 2024). Chinese restaurants began receiving negative press for the style of their cuisine. Writers described their food as “suspicious” and claimed the Chinese restaurants had unhygienic working conditions (http://conniewenchang.bol.ucla.edu/menus/index.html , December 8,2024). Americans rejected the Chinese establishments and called for the destruction of all Chinatowns. Because of this, Chinese restaurants began changing their cuisine.

Integration of American Culture in Chinese Cuisine

Yeh, Cedric. “Your Chinese Menu Is Really a Time Machine.” What It Means to Be American

Chop Suey kickstarted the acceptance of Chinese cuisine in American culture. This dish received positive news coverage and Americans are still very familiar with the dish (150 years of Chinese Cuisine in America). Chinese restaurants incorporated familiar ingredients such as broccoli, snow peas, carrots, and green peppers to appease to the American audience. They also included the word “Chinese” in their dishes, which allowed Americans to show off their open-mindedness and inclusivity for selecting a “foreign” dish. While these efforts made Chinese food successful in America, it also made the prejudices American had towards Chinese immigrants worse because they perceived their food and culture as something exotic or foreign without having an informed understanding of Chinese culture. While Chinese immigrants were able to establish themselves in America, their culture was not properly established due to the pressure to conform to American culture to find success.

Findings of our Investigation

A study on Chinese resturant longevity and success in the United States

“Let Us Have No More Chinatowns in Our Cities.”

Oakland Enquirer, April 1906.

Our investigation aimed to answer the question “which restaurants represented in the FS Louie collection have the greatest longevity, and what factors led to their success?” We began our search by measuring “success” through restaurant longevity and defining longevity as the amount of years which the restaurants were in business. From a vast collection of data from the F.S. Louie collection we selected the 24 restaurants with concrete opening and closing dates, and from there divided the data into restaurants open more than thirty years (which we defined as “long lived” and successful) and restaurants open less than thirty years (which we defined as “short lived” and less successful). We chose to compare these restaurants based on location because we wanted to understand which environments were most conducive to a successful restaurant. We also compared cuisine type to see if menus that catered to an American palette were more successful. The first diagram (below) visualizes our average restaurant longevity in each state that data was located in and appears to show no recognizable patterns between longevity and states. This suggests that the state a restaurant is located in may not play much of a role in their longevity.

This diagram shows the average longevity of a restaurant in each state featured in our data from restaurants represented in the FS Louie collection. While this is a helpful visualization, it is skewed and limited by the number of restaurants from each state, with some states that were more frequent FS Louie customers (California and Washington) that were had significantly more data in the set compared to other states that only had one restaurant.

However, the diagrams which reflect the cuisines of the long lived and short lived restaurants, respectively, show that the restaurants which were open for longer overwhelmingly served Chinese-American cuisine, while the shorter lived restaurants featured less Americanized food such as Chinese cuisine, Chinese-Mexican fusion and other fusions. This preliminary analysis aligns with the scholarly sources which we researched regarding historic public perception of Chinese immigration and the push for cultural assimilation within this population that was often reflected in changes such as the Americanized cuisine we see within our data.

Works Cited

Arnold, Bruce Makoto, Tanfer Emin Tunc, and Raymond Douglas Chong, eds. Chop Suey and Sushi from Sea to Shining Sea: Chinese and Japanese Restaurants in the United States. 1 ed., Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/book59042

Arthur, Chester, and US Congress. Chinese Exclusion Act, 1882. Chang, Rachel. 2023. How American Chinatowns Emerged Amid 19th‐Century Racism | HISTORY. https://www.history.com/news/american-chinatowns-origins

“Chinese Government Certificate of Return for Mah Chung.” DocsTeach, September 27, 1892. https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/mah-chung-certificate

“Chinese Immigration | History Detectives.” n.d. PBS. Accessed December 8, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/feature/chinese-immigration/

Delstein, Sally E. “The Occidental Oriental.” Envisioning The American Dream, April 10, 2014. https://envisioningtheamericandream.com/2014/04/10/the-occidental-oriental/

Frenzeny, Paul. Chinese Immigrants at the San Francisco Custom-House. Print. Harper’s Weekly Journal of Civilization, 1877.

Keller, George Frederick. “What Shall We Do with Our Boys?".” Cartoon. The Wasp. San Francisco, March 3, 1882.

Kiger, Patrick J. n.d. “How White America Tried to Eliminate Chinese Restaurants in the Early 1900s.” How Stuff Works. Accessed December 12, 2024. https://history.howstuffworks.com/historical-events/early-20th-century-america-war-on-chinese-restaurants.htm

“Let Us Have No More Chinatowns in Our Cities.” Oakland Enquirer, April 1906.

Liu, Haiming. From Canton Restaurant to Panda Express: A History of Chinese Food in the United States. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2015. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/41535.

Nast, Thomas. Pacific Chivalry. Cartoon. Harper’s Weekly, August 1869.

Ng 伍穎華, Laura W. Between South China and Southern California: The Formation of Transnational Chinese Communities. In Chinese Diaspora Archaeology in North America, edited by Shelley M. S. J. Li, 123-145. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2020. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/73271

“Olympia's Historic Chinese Community – Chinatowns – Olympia Historical Society and Bigelow House Museum.” n.d. Olympia Historical Society. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://olympiahistory.org/olympias-historic-chinese-community-chinatowns/

“Rice Bowl Exterior.” Museum of Chinese America (MOCA) Collection. 大同酒家外观;陈雪瑛捐赠,美国华人 博物馆(MOCA)馆藏 June 20, 2019.

Wan, Qin. n.d. The History of Chinese Immigration to the U.S. Accessed December 8, 2024. https://www2.hawaii.edu/~sford/alternatv/s05/articles/qin_history.html

Yeh, Cedric. “Your Chinese Menu Is Really a Time Machine.” What It Means to Be American, March 24, 2015. https://www.whatitmeanstobeamerican.org/artifacts/your-chinese-menu-is-really-a-time-machine/