Route 66: St Louis, MO

After a long stretch of highway through smaller cities with no large Chinese American presence, the Louies would arrive in St. Louis. Chinese Americans had been a large presence in St. Louis by the last part of the 19th century, with over 250 migrants arriving in 1869 for factory work, and by the 1920s, close to 1000 persons of Chinese ancestry made the city their home. Two restaurants, Chu Wah and the Peach Garden, both on Olive Street, bought bespoke Louie ceramics. The area of Olive Street is still known as the closest thing the city has to a Chinatown since the 1966 demolition of the historic Chinatown for the construction of a stadium. A third local restaurant that purchased Louie bespoke wares was the Lotus Room, in nearby Richmond Heights.

Chu Wah

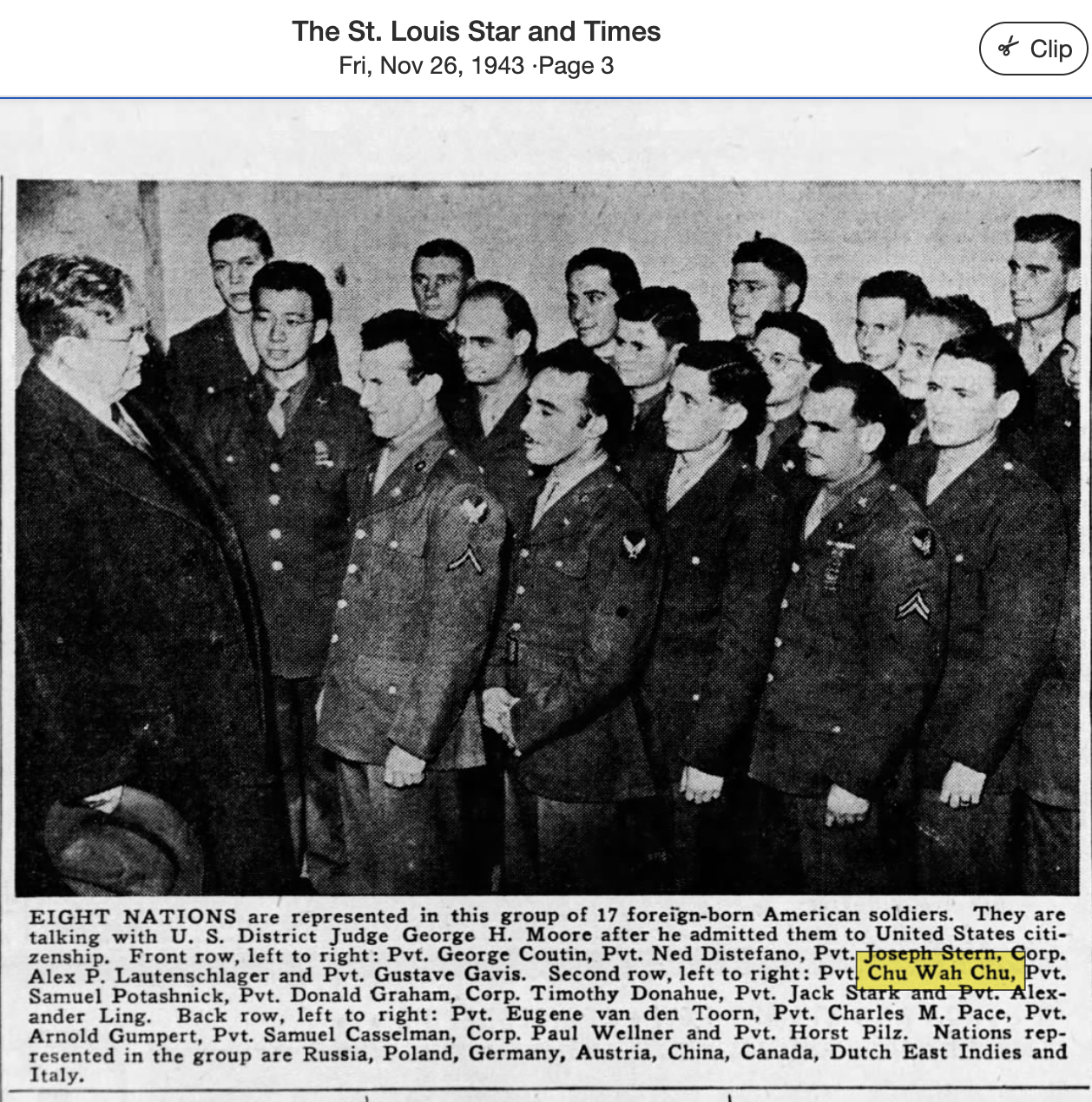

A newspaper article in the October 6, 1957, St Louis Globe-Democrat announced the opening of a new Chinese restaurant in the Olivette Shopping Center—the Chu Wah Restuarant. Chu Wah Chu and Oleta Chu, his wife, were owners of the restuarant. The article identifies Chu as the son of Quin Chu, who had run another St. Louis Chinese American restuarant. Quin’s obituary described him as the “unofficial Mayor of Chinatown”, a title seemingly given by the press to high profile Chinese American citizens in any number of cities, and succeeded in keeping Chinese Americans categorized as somehow outside of regular categories of citizenship. It was perhaps, in part, his father’s notoriety that led Chu Wah Chu to be included in a photograph of World War II soldiers in a local paper in 1943.

In articles announcing the opening of “Chu Wahs’s”, Chu was identified as a military veteran who had lived in the US since he was 7 years old. The article also emphasized the modernity of the kitchen appliances, including stoves and ingredients brought from Hong Kong and Formosa. A year later, June 12, 1958 article in the News-Times discussed both Chu’s long experience as a cook (20 years working for his father) and his 1949 return to Hong Kong, seeking an education in the most fashionable of food there. With 170-person capacity, and what was described as the only restuarant in the area with a cocktail lounge, Cuh Wah was seeking to provide a dining experience.

1959 advertisement; no sign of a log or specialized branding for the restuarant. The Restaurant and lounge is advertised in simple block letters with no illustrations.

THe little server first shows up in a mother’s day advertisement in a local Jewish newspaper. The restuarant only advertised when it was holiday occasions.

1974 advertisement for the restaurant, now featuring the “traditionally clothed” server. In his hands he carries two trays, one with pineapple tiki drinks, the other with food. This matches the figure on the matchbook.

One characteristic of the wares sold by Louie is the potential for multiple kinds of expression—the choice of font, the pattern selected, the embellishments or additon of personalized logos—all attributes of the wares that hint are larger concerns and experiences of Chinese American restaurant owners, workers, and how they communicated to one another and to their customers. Expressions of infrapolitics—or everyday acts of resistance used by marginalized groups—appear in different ways in the ceramic assemblage. In the case of Chu Wah Chu, who clearly identified himself within his community and through his restaurant name, as Chu Wah, with his surname in its proper placement (first), was known in all of his engagements with the non-Chinese American population of St. Louis as Chu Wah Chu…using his family name in both the Chinese and European position relative to his personal name in a way that was both pointed and humorous.

The FS Louie ashtray from the restaurant, as well as a matchbook obtained from the restaurant, both feature the representation of a Chinese server whose costume aligns him more with the imperial 19th century than the mid-20th century. On the ashtray the figure holds two trays, one with what appears to be two fizzing glasses of champagne, the other with food. The arrangement of the restaurant name is different than the print advertisement, but its impossible to know if the differences are due to temporal changes in the design or variation from the needs of designing for ceramic versus paper.

Before we talk about the imagery, I was to make a quick temporal detour. The ashtray features the older style exchange phone number with the exchange letters followed by the number rather than the full number version of the number. The advertisements feature a full number phone number. Based on newspapers, the shift from exchange to full digits was happening in 1969/1970. During those years newspaper advertisements in St. Louis used both style of phone numbers. In fact, Chu Wah simultaneously advertised for waitresses in the classified section with the exchange number and for customers with the new number. Perhaps the ashtrays were ordered in 1968 or 1969 before the transition began. There is nothing to suggest that the logo existed before 1970, thus we may have insights into when the Louies made this particular sale!

Photograph taken between 1896 and 1911 showing three Chinese immigrants in traditional work gard and shoes, teding to three small children. The men’s dress is clearly of the sort evoked in the ashtray image. Intriguingly, none of the men have a visible queue, a feature of hair style from the imperial period.

Let us turn to the figure. The figure is an anachronism. He wears neither modern garb of American or Chinese society. Instead, it harks back to laborer’s clothing of the late 19th century, including a clear tiny queue, a hair style associated with the imperial period of China. Why have the Chus decided to engage in a clear auto-Orientalization with this selection of a logo? When the restuarant opened, the couple emphasized the modernity and contemporary nature of their restaurant. By the time Chu Wah Chu’s father died in 1976, he is listed as a survivor but not described as the owner of a restuarant like his father. There is no evidence of the restaurant appearing in newspapers past 1974. This suggests that the little server was introduced as part of a rebrand to renew interest in a restaurant that was losing clientele. The disappearance of the restaurant from the historical record suggests they were not successful.

The Peach Garden

The Peach Garden predated Chu Wah, and was associated with another individual who had deep roots in St. Louis’ Chinese American population. The Peach Garden Restaurant was opened in 1940 under the ownership of a conglomerate lead by Sit Hom Yuen. Sit was already a well known figure in St. Louis. He appears in local papers in 1916, when he made news as the only Chinese American to register to vote in the Presidential election. The St Louis Post-Dispatch reported that of about 650 Chinese men who lived in the city, only about a dozen were American-born. Sit, who had apparently arrived in St. Louis around 1910, was born in San Francisco, and a member of the Chinese American-Born Alliance of San Francisco. The Alliance had written to him and advised him to register, which he had, showing a passport that he used to travel between the US and China to prove his citizenship. In 1921, Sit, described as the owner of the Oriental Tea and Mercantile, was presiding over the local chapter of the Chinese Nationalist League when they expressed their enthusiasm and congratulations to Dr. Sun Yat Sen on the occasion of his election to the presidency of the Republic of China.

An 1916 photograd of Sit Hom Yuen casting his presidential vote for Woodrow Wilson,

An early advertisment for the Peach Garden that ran in 1942. Note that the restuarant advertised an After-theater special.

The Peach Garden advertised chop suey and American dishes. During World War II, Sit regularly appeared in local papers when making large investments in War Bonds. He cultivated a public image that emphasized his love for the US and his strong patriotism. Starting in 1950, the Committee on Racial Equality [CORE] ran regular advertisements in local papers listing restaurants that welcomed everyone regardless of race. On lists published between 1950-1958, the Peach Garden always appeared. The list was extremely short–for example, in 1958, Peach Garden, Howard Johnson’s (all but one location in the city), White Castle and the Grand Inn were the only restaurants on the list. At a time when Jim Crow dominated, a Chinese American owned business, also potentially subject to racialized discrimination, could not have made the decision to commit to racial equality lightly.

1958 Advertisement placed by St Louis’ chapter of the Committee of Racial Equality, showing that Peach Garden was open to all.

By the 1950s, Sit’s daughter, Mary Sit Lou, was listed as co-owner of the restaurant. Ms. Lou had married a University of Pennsylvania educated economist who was a professor at Lim Nang University in Canton. Newspapers described her as having first travelled to China as a child with her parents. The couple had 6 daughters who they were raising in China when the communist take over happened. Mary was in the US with one of the children, and the couple found themselves separated. Dr. Lou quit his university position , being unwilling to teach for the communists, quit his job and escaped with five daughters to Hong Kong. Eventually the family was able to join Lou’s mother in Bangkok. It wasn’t until 1957 that the family was able to be reunited in St. Louis. The restaurant does not appear in newspapers after 1964.

Sue Sit, granddaughter of Sit Hom Yuen, covered in the local newspaper as “Girl Saturday”, a weekly feature in the paper.