Student Spotlight: "Ceramics of Identity”

"Ceramics of Identity: Regional Stories in FS Louie Ceramics (1950–2010)" by Anusha Muralikrishna, Pasha Zack, Rhea Jatakia, Alexis Guan, and Naomi Wang-Geffriaud

Introduction: Stories in the cups we drink from

Chinese-American restaurants are the heart and soul of U.S. multicultural dining. The blend of flavors, traditions, and history creates the delicious dishes we know today. But while our focus when we dine out is on the divine taste of the Oolong or Black tea themselves, did you know something as simple as the cups used to hold them tells us an equally rich story? These vessels are more than functional; they are cultural artifacts that reveal how Chinese-American communities balanced their identity while adapting to diverse regional markets across the United States.

Our team’s research explored FS Louie ceramics, a major supplier of Chinese-American restaurantware in the 20th century. From dragons symbolizing strength to birds representing joy, these intricate designs carried profound cultural meanings. But, they also reflected local economic realities and demographic diversity, changing depending on whether a restaurant operated in a bustling Chinatown or a small Southern town.

Through the lens of these ceramic artifacts, the smallest details–like a dragon curling across an ashtray—reveal to us the resilience of these communities as they navigated cultural preservation and adaptation.

The legacy of FS Louie: A supplier of symbolism

Founded in Berkeley, California, in the 1950s, the FS Louie Company revolutionized Chinese-American restaurant ware. Instead of offering plain white china, he introduced colorful pieces adorned with traditional Chinese motifs, each carrying a deep-rooted meaning.

Designs ranged from the ‘Dragon and Phoenix” which symbolize power, unity, and renewal, ‘Bird and Flower’ which represent joy, harmony, and the beauty of nature, ‘Two Women’ which depict unity and family values, to the ‘God of Longevity’ that is a portrayal of prosperity and long life (F.S. Louie & Co, 1960).

These motifs were not merely cultural markers but also a means for restaurants to choose patterns that reflected their heritage whilst simultaneously catering to the preferences of their regional audiences.

The Far West - A tapestry of heritage

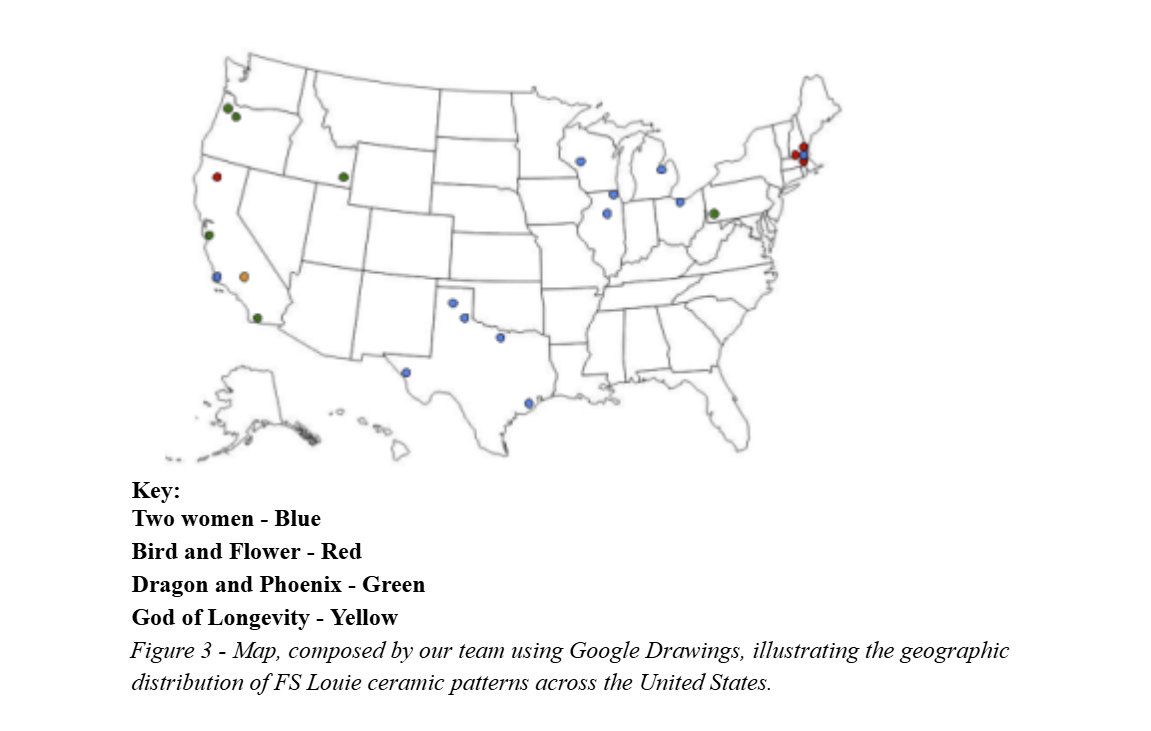

California is home to the oldest and most established Chinese-American communities. Cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Portland were cultural hubs where Chinatowns serve as symbols of cultural pride, as shown in our map below:

FS Louie ceramics in this region feature a mix of patterns (Figure 3), due to the fact that California has the earliest history of immigration which resulted in a uniquely multicultural society compared to the other regions. No single group dominated the population for long periods, which led to a blending of aesthetics and a need to cater to a broader audience. In addition, California’s position as a coastal state and its role in international trade meant attracting a wide range of visitors and residents with differing tastes. Furthermore, California is known for valuing individuality and self-expression, and offering multiple designs ensured that customers could choose patterns that resonated with their identity or heritage.

The Dragon and Phoenix pattern, deeply rooted in tradition, holds strong appeal for Chinese-American communities in places like San Francisco’s Chinatown and Monterey Park in Los Angeles, where cultural symbols of strength, renewal, and unity remain significant. Jimmy Wong of Jimmy Wong’s Golden Dragon, located in San Diego, gravitated towards these more traditional motifs, even selecting Dragon and Phoenix cups with an extra peacock design – no wonder, as he also painstakingly hand-painted a huge golden dragon running down the ceiling of his restaurant, along with designing the huge neon dragon sign outside his restaurant. His journey and cultural pride have been called an “immigrant success story” (Dean, 2012). Often featured in weddings, banquets, or festivals, the Dragon and Phoenix motif resonates with those valuing heritage and cultural pride, reflecting California’s broader identity as a state of reinvention, resilience, and prosperity. Meanwhile, the Bird and Flower design bridges cultural gaps, resonating with both Asian and non-Asian audiences through its universal symbolism of joy, beauty, and prosperity, aligning with California’s love for natural beauty and environmental consciousness. One example of a restaurant that chose this design is Sunnyvale’s Rice Bowl; their food was an early example of Americanized or even fusion food, as owner Howard Fong proudly advertised his “Burritos and Tofu Burgers” in 1988 (Emerson, 2024). Lastly, the Two Women motif caters to younger, more cosmopolitan, and diverse demographics in urban hubs like San Diego, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, thriving in eclectic, artistic settings such as trendy cafés and contemporary homes. Its modern, decorative appeal celebrates California’s creativity, diversity, and embrace of universal themes like femininity and relationships. Together, these patterns reflect the state’s cultural inclusivity, aesthetic sensibilities, and evolving identity. The God of Longevity pattern, a traditional motif symbolizing health, prosperity, and long life, resonates with communities that value heritage and intergenerational blessings. In California, this design would appeal particularly to Chinese-American families and older generations in areas like San Francisco’s Chinatown and the San Gabriel Valley, where traditional values and cultural continuity are celebrated (Lynn, 1995).

The East - Tradition in the Old Chinatowns

On the East Coast, cities like Boston and New York housed concentrated yet small Chinese-American communities (Figure 2) that sought to maintain cultural ties, and their ceramics reflect this emphasis on tradition.

The Bird and Flower pattern dominates East Coast restaurants (Figure 3), as shown in our map below, with the peony representing wealth and feminine beauty, alongside magpies to bless diners with good fortune. These motifs symbolized harmony, success, and a connection to Chinese roots. These patterns served as visual reminders of heritage, fostering solidarity in tightly-knit urban communities where preserving their culture was paramount. The Bird and Flower pattern likely traveled with these communities, its themes of harmony and prosperity helping small-town restaurants evoke a sense of connection to industrialized urban centers.

Unlike West Coast immigrants who arrived early during the Gold Rush, East Coast Chinese communities tended to grow later and were more urbanized, with immigrants seeking economic opportunities in cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia (East/West, 1976). These communities often came from similar regions in southern China such as Guangdong, leading to a stronger cultural cohesion and a more unified aesthetic in patterns like Bird and Flower. These smaller, more dense communities compared to the large and dispersed Californian ones meant people were seeking a sense of home and comfort amongst the rapidly changing scene of the East Coast. After facing exclusionary policies and economic barriers that were more stringent than in the West (as these communities were fewer), the pattern’s themes of resilience and prosperity would resonate with the people as they sought to establish themselves in America (Hayes, 1882).

Moreover, the East Coast, with its appreciation for fine craftsmanship and classical design, would be drawn to the intricate details of the Bird and Flower pattern.

The South and Midwest - Adapting tradition and westernization

In Southern and Midwest states, on the other hand, the ‘Two Women’ pattern appealed to a more Westernised audience (Figure 3). These communities were few and far between (Figure 2). Rather than being centralized Chinatowns, the restaurants were separated and less populated than those on the East and West Coasts. This is a representation of the racial discrimination and American patriotism that was demonstrated in opposition to the Chinese people (Hayes, 1882). As immigrants arrived in these regions much later, they catered to a more Westernized palate and cultural expectations, adapting their food, restaurant aesthetics, and marketing strategies to fit Southern preferences (e.g. Fried chicken Chow Mein deals) (The Bellaire Texan, 1958). These limited communities meant restaurant owners had to appeal more specifically to non-Chinese diners to earn money, focusing on a Westernized Chinese cuisine (such as Chop Suey, which is not found in local Chinese restaurants) as opposed to the traditional ones seen in Chinatowns in the West and East.

In many Southern and Midwestern cultures, storytelling is a cherished tradition. The ‘Two Women’ and its elements that tell a story of family and friendship deeply resonated with these audiences. Values of unity, where women in particular are often seen as central to family create a cross-cultural connection and the more conventional portrait of Chinese attire may be more approachable for an audience unfamiliar with purely traditional designs, hence creating a more welcoming and accessible dining atmosphere.

The Pacific Northwest- A blend of Traditional and Local Inspiration

In the Pacific Northwest, FS Louie Ceramics reveals a unique blend of traditional and Chinese motifs and locally inspired designs, reflecting the dual identity of Chinese-American communities in this region. While the traditional Dragon and Phoenix pattern symbolizing power, harmony, and unity remained a favorite among Chinese restaurant owners, local variations also emerged (Figures 2 and 3).

Custom patterns featuring orange and blue flower designs mirrored the vibrant native wildflowers of the Pacific Northwest (e.g. Lewis Flax) creating a visual connection to the region’s natural beauty. These designs demonstrate how Chinese-American restaurant owners adapt to their new environment and blend their cultural heritage with geographic identity.

In cities like Seattle and Portland, where Chinese communities were well-established, traditional patterns like Dragon and Phoenix dominated, serving as a powerful symbol of cultural pride. These designs resonated particularly in urban Chinatowns, where they reinforced community identities and celebrated the values of resilience and prosperity.

In small towns, however, the floral patterns catered to a broader audience, which reflects an effort to appeal to non-Chinese customers while still honoring tradition. This adaptability shows the creativity of Chinese-American communities as they navigated the challenges of preserving their heritage while forging connections with their new neighbors.

Conclusion:

The artifacts of FS Louie tell a profound story of identity, adaption, and creativity within Chinese-American communities across the United States. Each regional dominated or special design —whether the Dragon and Phoenix in California, the Bird, and Flower on the East Coast, the Two Women in the South and Midwest, or the floral design of the Pacific Northwest (as shown in our maps)— reflects the Chinese community’s response to its environment. These artifacts reveal how Chinese immigrants balanced cultural heritage with local influences. More

than just tableware, FS Louie artifacts stand as tangible expressions of cultural pride and serve as windows into the lives of the Chinese-American community.

References:

East/West. 1976. "F. S. Louie, an Industrious and Innovative Entrepreneur." East/West, November 24, 7.

1960. F. S. Louie & Co. Catalogue. Berkeley: F. S. Louie Company.

Jeffrey, Dean. “Jimmy Wong’s Golden Dragon, San Diego, CA.” Flickr, August 19, 2012. https://www.flickr.com/photos/29276830@N02/7815831900/in/photostream/.

Emerson, Bob. “San Jose History: Tao Tao Cafe Sunnyvale.” Facebook. Accessed December 10, 2024.

Pan, Lynn. 1995. True to Form: A Celebration of the Art of the Chinese Craftsman. Hong Kong: Form Asia Books. https://www.facebook.com/groups/SanJoseHistory/posts/2316868861777668/.

U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian. "Chinese Immigration and the Chinese Exclusion Acts." Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations. Accessed December 16, 2024. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/chinese-immigration.